This piece explores a woman's subjectivity and her relation to the external world. In the film, Deren walks into her home and falls asleep in an armchair in the living room, and while in this trance or dream like state she is forced to confront her fears. There are key elements that repeat in this film, like objects such as a key, a knife, a telephone, mirrors, and a hooded figure. In one scene, Deren is outside and spots the hooded figure at the end of the driveway. Just like in a dream, she tries to chase the person down, but is unable catch up to them. Eventually she ends up seeing this hooded figure in her bedroom, placing a flower on her pillow.

When it turns around the figure is not a person but rather has a mirror as a face. Dreams symbolize our subconscious thoughts and anxieties, and this concept is prevalent in the film. After going through an array of bizarre occurrences Deren is awoken by her husband, who brings her back to reality in a sense and she is upset by this. I think that she chose this to display the normalized ideal in Hollywood that a man is the hero of a story, like it was his duty to save the woman character in the film. Likewise, it displays the typical role of women in film, to play the helpless female who needs a man to protect her. Her husband then leads her upstairs to their bedroom and places a flower on her pillow, just like the mirror faced figure did. In that moment the knife, an object that is repeated in the film, appears in her hand and she moves to stab her husband in the face. When doing so, he shatters into pieces like a mirror would.

This is displaying her need for freedom from the domesticated life she lives. Throughout the film Deren chooses to take different paths to try and find a solution to her problems with traditional views of relationships and women being confined to their homes. As Deren continues to choose different paths in her dream state, she gets closer and closer to the freedom which she seeks, but the dream keeps trying to keep her away from her goal.She need to be free, and the film displays that death is the only way to freedom from the tyranny of a male dominated world.

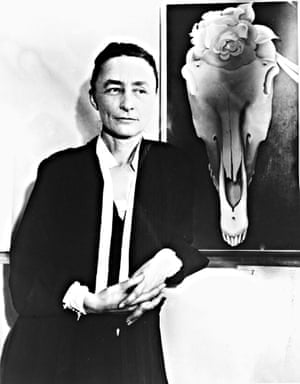

With Darren's experimental style of filming and her stance on feminism and women's rights in the 40s and 50s she is an inspiration to all filmmakers and especially to me. In the way that she reframed female issues through her films while infiltrating and repurposing masculine art forms, Deren cemented herself as an important female artist, director and filmmaker. If you are interested in watching the short film, here is a link to the free vimeo version. Meshes of the Afternoon