“I have already settled it for myself so

flattery and criticism go down the same drain and I am quite free,” as she once

said. “Someone else’s vision will never be as good as your own vision of your

self.”

– Georgia O’Keeffe

When one thinks of

prominent female artists, Georgia O’Keeffe is undoubtedly in the top five of

most people’s list. Despite entering a field dominated by male artists,

curators, gallery owners, she was able to establish herself as one of the

foremost female artists of the 20th century, with a distinct

artistic style all her own. Once O’Keeffe moved to New York she had several

gallery exhibitions, but her first retrospective was in 1927 at the Brooklyn

Museum, featuring her most famous artistic subject-her flower close-up

paintings which she produced throughout the 1920’s. Her body of work spanned

seven decades, participating in the beginning of the American Modernist

movement, her paintings of flowers and desolate landscapes were portrayed

through an abstract lens conveying the emotional power of the objects.

Her most famous paintings were of course her magnified,

large-scale exploration of flowers, which many at the time and still continue

to argue is actually representative of female genitalia. O’Keeffe herself has

vehemently denied this one-dimensional sexist assumption/interpretation of her

paintings. In recent years, O’Keeffe’s work has had a large retrospective at

the Tate Modern in London. The Tate Modern’s director of exhibitions said this

of O’Keeffe’s work:

“O’Keeffe has been very much

reduced to one particular body of work, which tends to be read in one

particular way…Many of the white male artists across the 20th century have the

privilege of being read on multiple levels, while others – be they women or

artists from other parts of the world – tend to be reduced to one conservative

reading. It’s high time that galleries and museums challenge this.”

Georgia O’Keeffe herself bucked against this

sexist reading of her work, especially since most of the art critics of her day

were white upper-class men. If her paintings were in fact an exploration of

female sexuality, they greatly differed from the display of sexuality by male

artists, as explored in “Ways of Seeing” by John Berger: “Her body is arranged

in the way it is, to display it to the man looking at the picture. This picture

is made to appeal to his sexuality. It has nothing to do with her sexuality.”

(55) Of course male art critics of the day, used to females being painted in a

way that only appealed to their lens of sexuality, would have a problem with

O’Keeffe’s soft but emotionally powerful exploration of the female subject. Clearly

this criticism didn’t effect Georgia’s work or popularity, as she recently set

the record for the most expensive

artwork sold by a female artist at auction (44.4 million).

|

| O'Keeffe's record setting work sold at auction for $44.4 million |

Paul

Rosenfeld, a more enlightened male critic, spoke of O’Keeffe’s work as such: “No man could feel as Georgia O’Keeffe and utter

himself precisely in such curves and colors; for in those curves and spots and

prismatic color there is a woman referring the universe to her own frame…

rendering in her picture of things her body’s subconscious knowledge of itself…

What men have always wanted to know and women to hide, this girl sets forth.”

The power of her paintings stem from her mastery of line, composition, and

color. Her paintings seem to have a vibrant glow that capture the emotion of

commonplace subjects. What made her such

a gift to feminism and the art world was the fact that she didn’t let her

status of being a female artist define her work. Much as Judith Butler affirmed

in her piece ‘Gender Trouble’; “If one ‘is’ a woman, that is surely not all one

is; the term fails to be exhaustive” (5). O’Keeffe wanted her work to transcend

her gender, a principle she brought to every aspect of her life.

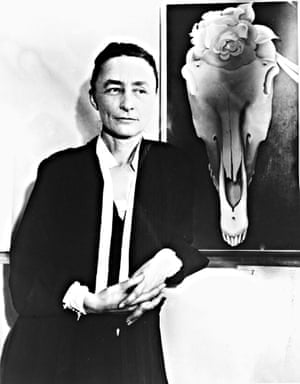

|

| O'Keeffe's signature androgynous style |

She rebelled

against her label as a strictly female artist with her stark, androgynous and

almost masculine everyday style documented throughout her life. Since there was

such a gender divide in the art world at the time, she seemed to buck against

that by removing gender from her work and personal

style, a true original in every sense of the word. The concept of Feminist

Masculinity seems to be in line with O’Keeffe’s views : “Feminist masculinity does

not come at the cost of femininity, it is a contextually specific enactment of

self that embraces the complexity of gender expression, a way to conceptualize

performances of masculinity in tandem with performances of femininity.” (47)

-Butler, Judith. “Gender Trouble: Subjects of

Sex/Gender/Desire” Routledge, 1990.

-Nydia Pabon-Colon, Jessica. “Performing Feminism in the Hip

Hop Diaspora” NYU Press, 2018.

-Berger, John. “Ways of Seeing” Penguin Press, 1972.

No comments:

Post a Comment